Skate

Sharpening Information for freestyle and dance skaters.

I have listed below often

asked questions and their answers with the goal to take some of the mystery out

of skate sharpening and help skaters make knowledgeable decisions about the

sharpening of their skates.

Besides needing to have a

very good and accurate sharpening machine, the sharpener needs to be a skilled

craftsperson with a method that makes the sharpening consistent and with a “feel” for the actual sharpening.

The answers below come from

over four years of sharpening or working with very good sharpeners. As one of the very few sharpeners that

actually currently skates and competes I have a good understanding of many of

the concerns and anxieties of having ones skates sharpened. Technical information was taken from Sidney

Broadbent’s book “Skateology” and many of the questions and answers came from a

list by Charles Wright.

When reading the

questions and the answers, you have a question that is not answered or a comment

or suggestion on any of the responses, please email them to me. Send

Email Question or Comment.

Often asked questions:

How

does the blade move or slide over the ice?

Why

does the blade turn when I lean?

What

is the correct hollow for me?

What

is the difference between a dance and freestyle blade?

How is

a skating blade sharpened?

Is

the toe pick ever sharpened?

Why

does the area behind the toe pick not have a hollow?

Why

are some blades not flat on the sides?

How

often should I have my skates sharpened?

Are

new blades ready to skate on?

How

can I tell if the edges are level or square?

Should

I be concerned with nicks in the blade?

What

does a sharp edge look like?

What are templates and how are they used?

How

should I deal with my skate sharpener?

How

long should it take to break in newly sharpened skates?

My

blades feel and look sharp but they don’t feel secure?

How

can I check or monitor the quality of my sharpening?

Why

use guards or soakers on my blades?

What

are common sharpening flaws?

How does the blade move or slide over the ice?

If you apply pressure to

ice, it melts. When the blade presses

against the ice, it creates a thin film of water, which acts as lubricant to

allow the blade to slide. When you are

skating, you actually are skating on a thin film of water.

Why does the blade turn when I lean?

Next time you skate, glide

straight ahead on the blade. Using your ankle and nothing else, tilt the skate

to the right or left, and feel how it turns you in that direction. View the

blade from the side and notice how it curves up at the front and back (it has

"rocker"). Pressed into the ice, a short length of it is actually in

contact with the ice. As it is tilted onto an edge, you can probably envision

that this length of contact is slightly curved. As the blade moves along the

ice, it will follow this curve. The

curve will be deeper if you lean your ankle more. It will also be deeper if

your blade has more of a rocker, as most blades are toward the front. As

you glide on an edge, press slightly forward on it, and feel how it tries to

curve more.

What is the hollow?

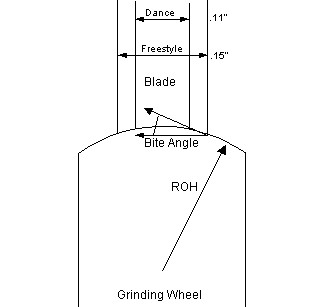

You probably know that your blade has two edges, inside and outside, and that there is a "hollow" between the edges. You may also know that the hollow can be "deep" or "shallow", and be able to feel the difference by running your finger across the blade. Refer to the following figure showing a cross section of a blade. The blade is made of a piece of steel of some thickness (a typical freestyle blade is about 0.15" thick). The bottom of the edge is ground out with a circular cross-section (see "how is a blade sharpened", below). The radius of the circle is called the Radius of Hollow (ROH). The shorter the ROH, the "deeper" the hollow. A blade with a deep hollow will hold the ice better, but will also be grabbier and slower.

What is the correct hollow for me?

This is a very individual matter. I

will state some facts, and then some opinions. An important thing to note is that

the ROH (see question "What is the hollow") does not tell the whole story about how a blade feels. The blade touches the

ice only along the edges, so what's really important is the angle between the

side of the blade and the bottom of the blade at the edge. Some blades are

wider than others. For example an MK Phantom is 0.155" wide, an MK Dance is

only 0.11" wide. If you have a geometric mind, you can probably see that,

given the same ROH on the two blades, the wider blade will have a sharper angle

at the edge. So, to give the same strength of edge, narrower blades will need a

shorter ROH.

A more acute edge angle (deeper

hollow) makes the blade less likely to slide sideways, so a deeper hollow gives

more secure edges. There is more to it than that, though. It also makes the

blade more determined at going where IT wants to go, so it will be harder to

control (more likely to grab or "catch an edge"). And, the deeper cut

into the ice causes more drag, so the blade will be slower. Given these

tradeoffs, one could state that the optimum ROH is one which is just deep

enough to give the skater the required edge security.

Learning proper use of the ankle to

control edges is important, and a shallower hollow facilitates this. As the

skater becomes more advanced, they are likely to use a deeper hollow to gain

security of the edge. This may be especially important to advanced freestylers

desiring edge confidence on jump takeoffs and landings. On freestyle

blades, I see ROHs varying

from 7/16" to 5/8". The

following graph shows bite angle versus ROH for various blade widths (The MK

Dance is 0.11" wide, Wilson Dance is 0.14" wide, most skates are

0.15" wide, Phantoms are 0.155" wide at their widest part). Given a

desired bite angle and the width of your blade, you can look up the radius of

hollow required to give that bite angle. A 10-degree bite angle is pretty deep,

and a 7-degree is fairly shallow.

Note that on side-honed blades,

(Phantom, Gold Seal and Gold Star) the side of the blade where it meets the ice

is cut at an angle to the plane of the blade, so the bite angle is effectively

increased by this amount. On side-honed blades this angle varies between

blades, but appears to be between 2 and 3 degrees. An exception is the Phantom

Special, on which the side is cut at an angle of about 9 degrees! Note that the

geometry is slightly different for this case, so the blade will behave

differently than one that simply has a very deep hollow.

What is the rocker?

If

you look at the blade from the side, you will see that it curves from front to back. This is

the rocker. Blade companies generally specify the "rocker

radius" for their different blades. If you draw a circle of this radius

(typically 7 or 8 feet), approximately the back 2/3 of the blade will have a

fairly circular contour that matches the arc of the circle with a 7 or 8-foot

radius. The radius of curvature decreases toward the front (there is more

curve), giving the blade a complex shape.

The

increased curve toward the front of the blade has an interesting effect. If you

move your weight forward on the blade while on an edge, it will want to turn on

a deeper edge. You may know that you spin on this part of the blade. You

probably have also felt how the blade can grab if you rock back on it while

spinning. A

long radius of curvature gives a faster, more stable blade. This is why speed

skates have very little rocker. It also gives less maneuverability, which is

a reason why figure skates curve more at the front. MK

blades are mostly specified to have a 7-foot radius and John Wilson blades have

an 8 radius specification. A

recent check of many new blades indicated that the MK blades were pretty close

to their specified 7-foot radius, while Wilson blades were closer to 6.

Of

more concern is the considerable deviation that is seen, in the form of local

"humps" in the rockers at various points on the blade, of both

brands. Their specified radius is not precisely controlled. A good sharpener can detect these “humps”

and usually correct the rocker. Of course, it is also quite possible that

careless sharpening can introduce such problems as well.

What is the difference between a dance and freestyle blades?

First,

dance blades are shorter. Dancers tend to do a lot of tight footwork, and the short heel

gives less to get tangled up (step on, lock with your partner's blades or your

own, etc.). Secondly, they don't tend to curve up as quickly on the front, so

they are not particularly good for jumps and spins. Also, they do not have the

pronounced toepick that is seen on freestyle blades, since they are not

expected to be used for jumping. Dance

blades are less forgiving than freestyle blades. Many dancers have experienced

getting their weight too far back and falling over backwards. Some styles or brands of dance blades are

narrower than freestyle blades.

What does the toe pick do?

There

are two parts of the toepick, the part that hangs down (the drag pick), and the

part that sticks out in front (the master picks). The drag pick is the last

thing to leave the ice on an axle, the first thing to touch on a jump landing,

and it just touches the ice on most spins.

If

you rock forward on the blade, you can only go so far before hitting the drag

pick. This forward most point is called the "Forward Balance Point".

When you spin, you are skating on this point, with the drag pick just touching

the ice. Because

of the drag pick, you cannot skate on the length of blade between the

forward balance point to the drag pick.

How is a skating blade sharpened?

The

skate is sharpened with a rotating grinding wheel. Prior to sharpening, the

wheel is "dressed" (using a special diamond-tipped tool) in such a

way that it has a circular cross-section (whose radius is the Radius of

Hollow). The skate blade is clamped into a holder, which holds its bottom surface

perpendicular to the grinding wheel. Your friendly skate sharpener moves the

clamped blade along the rotating grinding wheel to refresh the hollow in the

bottom of the skate. The sharpening machine has a special guide to keep the

blade perfectly aligned with the grinding wheel.

The

goal of the sharpening is to remove just enough metal from the bottom of

the blade to renew the edges. A steady hand is required, so that no part of the

blade is ground more than another.

Is the toe pick ever sharpened?

Yes.

You can see that after a blade has been sharpened many times, the profile of

the edge should be the same, but closer to the boot. If the drag pick (see question "What does the toepick do?)

has been

left untouched, the drag pick will be at a different relative position than

when the blade was new, and the skater's technique will change to accommodate

this. It is therefore desirable to occasionally remove tiny amounts of material

from the pick, so that the profile is retained.

Why does the area behind the toe pick not have a hollow?

This

area between the toe pick "drag pick" (see question "What does the toepick do?) and the forward balance point is a

non-skating zone that does not come in contact with the ice. Most new blades are not sharpened in this

area and thus no hollow. Large wheel

sharpening machines cannot sharpen in this area without hitting the toe pick

(drag pick). Sharpeners with small

wheel machines usually start their cutting in this non-skating area and even

the pressure as they move along the blade.

This is also less likely to cause a flat spot on the blade at the

forward balance area.

Why are some blades not flat on the sides?

Generally,

less expensive blades are of constant thickness, with flat sides. As you get

into the more expensive blades, you may see two features: they may be tapered

from front to back (wider at front, narrower toward back), and they may be

"side honed" (material ground from the sides so that instead of being

flat, they are concave).

Depending

on the blade design, side honing may create a sharper bite angle at the edge.

It definitely makes a blade harder to sharpen with level edges.

A

blade design variation worth noting is the "Coplanar" and “Ultma”.

These blades have the high quality steel and stronger construction of high-end

blades, but are of constant thickness throughout, thus easy to sharpen well. In

addition, they have a unique mounting geometry with certain claimed advantages

(because of their flat mounting plates, they can be repositioned on the boot

without changing the blade angle.).

How often should I have my skates sharpened?

"Before

they need it". It depends on how much you skate and how hard you skate. If

your edges are damaged or no longer feel secure, then it's certainly time to

get them sharpened. I try to remember that nice feel of freshly sharpened

skates, and when they don't feel that way, it's time. Generally, to keep the sharp feel all the time, and not have to

get use to just sharpened skates, have them sharpened between 20 to 30 hours of

skating. If you stay with the same

sharpener, sharpening often will be more like a touchup and, if done correctly,

the blade will still last five to eight years.

If

you examine the bottom of the blade right after sharpening, the bottom of the

blade will have a uniformly satin sheen. With more skating, the blade bottom

near the edge, under different light conditions, will begin to appear dull.

These lines along the edge of the blade are the starting of “flat spots” or a

“dull” blade.

Are new blades ready to skate on?

Figure

skate blades generally come from the factory already sharpened. My observation

is that this sharpening job is generally of low quality, unlevel edges and the

factory ROH (see question "What is the hollow") may or may not be appropriate for the particular skater. Always

sharpen new blades before skating on them or at least have them checked by your

skate sharpener.

How can I tell if the edges are level or square?

Ideally,

the centerline of the hollow is halfway between the two sides of the blade. If

it is not, one edge will be higher than the other and will have a sharper bite

angle. If too far off, the effect will be asymmetrical edge strength (for

example, inside edge grabby, outside weak), and flats that want to turn. Your

skate sharpener should always check that your edges are level after

sharpening. A common way to make a

rough check is to balance a coin (or other straight edge) on the bottom of the

blade and "eyeball" it. I think that this method is really too

imprecise to detect any but really gross errors. I use a miniature, precision

machinist's square to check that edges are square with the side of the blade.

Other devices for checking this are also made. Note that side-honed blades are

much more difficult to check, because the side of the blade is not flat.

Should I be concerned with nicks in the blade?

Not

really. It is extremely important that any deformation of the metal on the side

or bottom of the blade, next to the nick be ground away. I observe that a slight

"hole" in the edge is generally not noticeable, and, in the interest

of prolonging blade life, large nicks are generally not completely removed.

What does a sharp edge look like?

If you examine a sharp edge

in a strong light, you should see no reflection from the edge, even looking

with a strong magnifier.

What are templates and how are they used?

Templates

are like patterns or outlines of a blade to the manufacturers original

specifications. Templates are most

often used to restore a flattened rocker, damaged from bad sharpening.

How should I deal with my skate sharpener?

I

suggest that, once you find a skate sharpener that you like, stick with them.

The reason for this is simple. Every skate-sharpening machine has slight

differences. A blade can be resharpened on the same machine with minimal metal

removal, protecting your blade investment.

Each sharpener also has his own touch or feel for the sharpening.

You

should be prepared to interact a little with the person who sharpens your

skates. Hopefully, they will be willing to discuss any problems that you

perceive.

For

the first sharpening, find out how far off, if any, the blades are. Decide if you want them corrected in one

sharpening or over several sharpenings, or have your coach talk with your

sharpener and make these decisions.

Always leave your name and phone number with your skates to be sharpened,

in case the sharpener has questions for your sharpening.

Your

sharpener should keep detailed records of your skate sharpenings and be willing

to review them with you. After your

first sharpening, your sharpenener should be able to match exactly what you have

each time.

When

you buy new blades, take a few minutes to trace their contour on a piece of

paper. Occasionally, after sharpening,

compare each blade to this contour and note any visible changes to the rocker. In particular, if the same person has been

sharpening your skates, visible changes are something he would want to know

about.

How long should it take to break in newly sharpened skates?

Most

skaters are conditioned to expect a bit of an adjustment period after having

their skates sharpened. The common symptom is that skates feel

"grabby"; edges catch, and stopping is difficult. Skaters with newly

sharpened skates are often seen doing things like dragging their skates

sideways on the ice, running blocks of wood along their blades, etc., to dull

them into skateability. The correct

expectation is that properly sharpened blades should have little or no

adjustment period. They should never feel grabby. They should simply feel more

secure. (exceptions are those cases in which changes are made to a blade, such as

correcting previous sharpening errors or changing the depth of hollow, or

sharpening an exceptionally dull blade).

The

edge of a well sharpened blade should feel very smooth as a finger is run along

the edge; proper edge finishing will have removed the metal burrs that can

cause grabbiness, and give the edge a smooth, non draggy feel. Be careful: a

sharp blade can cut (though a well-finished blade is less likely to do so).

My blades feel and look sharp but they don’t feel secure?

This insecure feeling on sharp

blades can have several causes and possible solutions. Maybe you need a deeper hollow or the hollow

was made shallower on the last sharpening.

Talk with your coach and skate sharpener. It may be that you are ready for a deeper hollow. There are many pro and cons about using polish

on the last pass of the grinding wheel when sharpening skates. Many figure

skaters do not like the feel of a polished hollow. Decide on the use of polish for yourself, based on how it feels

when you skate and not on what others say.

How can I check or monitor the quality of my sharpening?

First,

you should be alert to any differences in the feel of the blade after

sharpening. Are your jumps or spins different?

Do the edges grab, especially one more than another? Discuss any feelings or differences with

your skate sharpener. This is where

having a sharpener, who also skates, will be a big plus.

Why use guards or soakers on my blades?

Guards should be used only when you

need to walk around when not on the ice.

Guards should not be on the blades any longer than necessary. Blades will start to rust in a very short

time when wet with the guards on.

Soakers should be on the blades anytime the skates are not on your

feet. Even though rinks have rubber

mats and various other materials around the rink to protect blades from damage

– NEVER walk on these materials with your blades. There is a lot of dirt from street shoes, etc. that will quickly

dull your blades.

How long should blades last?

If

I have previously sharpened a blade, I find that each sharpening removes only

about 0.001" of metal (a typical piece of paper is about 0.004"

thick) on a resharpening. If there is 0.1" of sharpenable depth on the

blade when new, this means that you might get as many as 100 sharpenings out of

a blade. With monthly sharpenings, this would give a blade life of up to 8

years. Sharpenings to restore edge level will take off much more metal. So will

sharpenings to change radius of hollow. I believe that skaters typically get a much shorter blade life, for various reasons. Still, a careful sharpener can do

much to prolong blade life and protect the skater's investment.

What are common sharpening flaws?

While

the goals for good sharpening are quite easy to quantify, skate sharpening is a

manual operation and as such is very much a "craft". The most often

seen flaw is unlevel edges. If the centerline of the grinder is not aligned

with the centerline of the blade, one edge will be higher (and

sharper/grabbier) than the other. The effect of this is that one edge will grab

while the other will feel weak. If really bad, the blade will pull to the right or

left.

To

achieve an even grind, the sharpener must move the blade along the rotating

wheel with constant force and speed. With time and repeated sharpenings, it is

possible that errors will accumulate and show up as uneven rocker. The degree

to which this happens is a measure of the skill of the sharpener. Sometimes a

particularly heavy hand in sharpening can alter this curve in one sharpening.

If when reading the

questions and the answers you have a question that is not answered or a comment

or suggestion on any of the responses, please email them to me. Send

Email Question or Comment.